baptist.party

A little too much coffee and Roberts' Rules.

Baptists & Religious Liberty

May 15, 2024BAPTISTS & RELIGIOUS LIBERTY

Introduction by J.B. Gambrell

“This address was arranged for weeks before the Southern Baptist Convention met in Washington. Washington City Baptists are directly responsible for it. The speaker, Dr. George W. Truett, pastor of the First Baptist Church, Dallas, Texas, was chosen by a representative group of Baptists to deliver the address. It was delivered to a vast audience of from ten to fifteen thousand people from the east steps of the National Capitol, at three o’clock on Sunday afternoon, May 16, 1920. It was not a Convention session, though the Convention was largely represented in the audience by its members.

“Since Paul spoke before Nero, no Baptist speaker ever pleaded the cause of truth in surroundings so dignified, impressive and inspiring. The shadow of the Capitol of the greatest and freest nation on earth, largely made so by the infiltration of Baptist ideas through the masses, fell on the vast assembly, composed of Cabinet members, Senators and members of the Lower House, Foreign Ambassadors, intellectuals in all callings, with peoples of every religious order and of all classes.

“The subject was fit for the place, the occasion, and the assembly. The speaker had prepared his message. In a voice clear and far-reaching he carried his audience through the very heart of his theme. History was invoked, but far more, history was explained by the inner guiding principles of a people who stand to-day, as they have always stood, for full and equal religious liberty for all people.

“There was no trimming, no froth, no halting, and not one arrogant or offensive tone or word. It was a bold, fair, thorough-going setting out of the history and life principles of the people called Baptists. And then logically and becomingly the speaker brought his Baptist brethren to look forward and take up the burdens of liberty and fulfil its high moral obligations, declaring that defaulters in the moral realm court death.

“His address advances the battle line for the denomination. It is a noble piece of work, worthy the wide circulation it is sure to receive. Intelligent Baptists should pass it on.

“A serious word was said in that august presence concerning national obligations as they arise out of a civilisation animated and guided by Christian sentiments and principles. As a nation we cannot walk the ways of selfishness without walking downhill. “T commend this address as the most significant and momentous of our day. “

J. B. GAMBRELL, “President Southern Baptist. Convention.”

ADDRESS BY G.W. TRUETT

WASHINGTON, D.C.

MAY 16, 1916

Southern Baptists count it a high privilege to hold their Annual Convention this year in the national capital, and they count it one of life’s highest privileges to be citizens of our one great, united country.

Grand in her rivers and her rills, Grand in her woods and templed hills; Grand in the wealth that glory yields, Illustrious dead, historic fields; Grand in her past, her present grand, In sunlit skies, in fruitful land; Grand in her strength on land and sea, Grand in religious liberty.

It behooves us often to look backward as well as forward. We should be stronger and braver if we thought oftener of the epic days and deeds of our beloved and immortal dead. The occasional backward look would give us poise and patience and courage and fearlessness and faith. The ancient Hebrew teachers and leaders had a genius for looking backward to the days and deeds of their mighty dead. They never wearied of chanting the praises of Abraham and Isaac and Jacob, of Moses and Joshua and Samuel; and thus did they bring to bear upon the living the inspiring memories of the noble. actors and deeds of bygone days. Often such a cry as this rang in their ears: “Look unto the rock whence ye were hewn, and to the hole of the pit whence ye were digged. Look unto Abraham, your father, and unto Sarah that bare you; for when he was but one I called him, and I blessed him, and made him many.”

THE DOCTRINE OF RELIGIOUS LIBERTY

We shall do well, both as citizens and as Christians, if we will hark back to the chief actors and lessons in the early and epoch-making struggles of this great Western democracy, for the full establishment of civil and religious liberty—back to the days of Washington and Jefferson and Madison, and back to the days of our Baptist fathers, who have paid such a great price, through the long generations, that liberty, both religious and civil, might have free course and be glorified everywhere.

Years ago, at a notable dinner in London, that world-famed statesman, John Bright, asked an American statesman, himself a Baptist, the noble Dr. J. L. M. Curry, “What distinct contribution has your America made to the science of government?” To that question Dr. Curry replied: “The doctrine of religious liberty.” After a moment’s reflection, Mr. Bright made the worthy reply: “It was a tremendous contribution.”

SUPREME CONTRIBUTION OF NEW WORLD

Indeed, the supreme contribution of the new world to the old is the contribution of religious liberty. This is the chiefest contribution that America has thus far made to civilisation. And historic justice compels me to say that it was pre-eminently a Baptist contribution. The impartial historian, whether in the past, present or future, will ever agree with our American historian, Mr. Bancroft, when he says: “Freedom of conscience, unlimited freedom of mind, was from the first the trophy of the Baptists.” And such historian will concur with the noble John Locke who said: “The Baptists were the first propounders of absolute liberty, just and true liberty, equal and impartial liberty.” Ringing testimonies like these might be multiplied indefinitely.

NOT TOLERATION, BUT RIGHT

Baptists have one consistent record concerning liberty throughout all their long and eventful history. They have never been a party to oppression of conscience. They have forever been the unwavering champions of liberty, both religious and civil. Their contention now is, and has been, and, please God, must ever be, that it is the natural and fundamental and indefeasible right of every human being to worship God or not, according to the dictates of his conscience, and, as long as he does not infringe upon the rights of others, he is to be held accountable alone to God for all religious beliefs and practices. Our contention is not for mere toleration, but for absolute liberty. There is a wide difference between toleration and liberty. Toleration implies that somebody falsely claims the right to tolerate. Toleration is a concession, while liberty is a right. Toleration is a matter of expediency, while liberty is a matter of principle. Toleration is a gift from man, while liberty is a gift from God. It is the consistent and insistent contention of our Baptist people, always and everywhere, that religion must be forever voluntary and uncoerced, and that it is not the prerogative of any power, whether civil or ecclesiastical, to compel men to conform to any religious creed or form of worship, or to pay taxes for the support of a religious organisation to which they do not belong and in whose creed they do not believe. God wants free worshippers and no other kind.

What is the explanation of this consistent and notably praiseworthy record of our plain Baptist people in the realm of religious liberty? ‘The answer is at hand. It is not because Baptists are inherently better than their neighbours—we would make no such arrogant claim. Happy are our Baptist people to live side by side with their neighbours of other Christian communions, and to have glorious Christian fellowship with such neighbours, and to honour such servants of God for their inspiring lives and their noble deeds. From our deepest hearts we pray: “Grace be with all them that love our Lord Jesus Christ in sincerity.” The spiritual union of all true believers in Christ is now and ever will be a blessed reality, and such union is deeper and higher and more enduring than any and all forms and rituals and organisations. Whoever believes in Christ as his personal Saviour is our brother in the common salvation, whether he be a member of one communion or of another, or of no communion at all.

How is it, then, that Baptists, more than any other people in the world, have forever been the protagonists of religious liberty, and its compatriot, civil liberty? They did not stumble upon this principle. Their uniform, unyielding and sacrificial advocacy of such principle was not and is not an accident. It is, in a word, because of our essential and fundamental principles. Ideas rule the world. A denomination is moulded by its ruling principles, just as a nation is thus moulded and just as individual life is thus moulded. Our fundamental essential principles have made our Baptist people, of all ages and countries, to be the unyielding protagonists of religious liberty, not only for themselves, but as well for everybody else.

Such fact at once provokes the inquiry: What are these fundamental Baptist principles which compel Baptists in Europe, in America, in some far-off seagirt island, to be forever contending for unrestricted religious liberty? First of all, and explaining all the rest, is the doctrine of the absolute Lordship of Jesus Christ. That doctrine is for Baptists the dominant fact in all their Christian experience, the nerve centre of all their Christian life, the bedrock of all their church polity, the sheet anchor of all their hopes, the climax and crown of all their rejoicings. They say with Paul: “For to this end Christ both died and rose again, that he might be Lord both of the dead and the living.” . From that germinal conception of the absolute Lordship of Christ, all our Baptist principles emerge. Just as yonder oak came from the acorn, so our many-branched Baptist life came from the cardinal principle of the absolute Lordship of Christ. The Christianity of our Baptist people, from Alpha to Omega, lives and moves and has its whole being in the realm of the doctrine of the Lordship of Christ. “One is your Master, even Christ, and all ye are brethren.” Christ is the one head of the church. All authority has been committed unto Him, in heaven and on earth, and He must be given the absolute pre-eminence in all things. One clear note is ever to be sounded concerning Him, even this, ‘““Whatsoever He saith unto you, do it.”

THE BIBLE OUR RULE OF. FAITH AND PRACTICE

How shall we find our Christ’s will for us? He has revealed it in His Holy Word. The Bible and the Bible alone is the rule of faith and practice for Baptists. To them the one standard by which all creeds and conduct and character must be tried is the Word of God. They ask only one question concerning all religious faith and practice, and that question is, ‘““What saith the Word of God?” Not traditions, nor customs, nor councils, nor confessions, nor ecclesiastical formularies, however venerable and pretentious, guide Baptists, but simply and solely the will of Christ as they find it revealed in the New Testament. The immortal B. H. Carroll has thus stated it for us: “The New Testament is the law of Christianity. All the New Testament is the law of Christianity. The New Testament is all the law of Christianity. The New Testament always will be all the law of Christianity.”

Baptists hold that this law of Christianity, the Word of God, is the unchangeable and only law of Christ’s reign, and that whatever is not found in the law cannot be bound on the consciences of men, and that this law is a sacred deposit, an inviolable trust, which Christ’s friends are commissioned to guard and perpetuate wherever it may lead and whatever may be the cost of such trusteeship.

EXACT OPPOSITE OF CATHOLICISM

The Baptist message and the Roman Catholic message are the very antipodes of each other. The Roman Catholic message is sacerdotal, sacramentarian and ecclesiastical. In its scheme of salvation it magnifies the church, the priest and the sacraments. The Baptist message is non-sacerdotal, non-sacramentarian and non-ecclesiastical. Its teaching is that the one High Priest for sinful humanity has entered into the holy place for all, that the veil is forever rent in twain, that the mercy seat is uncovered and open to all, and that the humblest soul in all the world, if only he be penitent, may enter with all boldness and cast himself upon God. The Catholic doctrine of baptismal regeneration and transubstantiation are to the Baptist mind fundamentally subversive of the spiritual realities of the gospel of Christ. Likewise, the Catholic conception of the church, thrusting all its complex and cumbrous machinery between the soul and God, prescribing beliefs, claiming to exercise the power of the keys, and to control the channels of grace—all such lording it over the consciences of men is to the Baptist mind a ghastly tyranny in the realm of the soul and tends to frustrate the grace of God, to destroy freedom of conscience and terribly to hinder the coming of the Kingdom of God.

PAPAL INFALLIBILITY OR THE NEW TESTAMENT

That was a memorable hour in the Vatican Council, in 1870, when the dogma of papal infallibility was passed by a majority vote. It is not to be wondered at that the excitement was intense during the discussion of such dogma, and especially when the final vote was announced. You recall that in the midst of all the tenseness and tumult of that excited assemblage, Cardinal Manning stood on an elevated platform, and in the midst of that assemblage, and holding in his hand the paper just passed, declaring for the infallibility of the Pope, said: “Let all the world go to bits and we will reconstruct it on this paper.” A Baptist smiles at such an announcement as that, but not in derision and scorn. Although the Baptist is the very antithesis of his Catholic neighbour in religious conceptions and contentions, yet the Baptist will whole-heartedly contend that his Catholic neighbour shall have his candles and incense and sanctus bell and rosary, and whatever else he wishes in the expression of his worship. A Baptist would rise at midnight to plead for absolute religious liberty for his Catholic neighbour, and for his Jewish neighbour, and for everybody else. But what is the answer of a Baptist to the contention made by the Catholic for papal infallibility? Holding aloft a little book, the name of which is the New Testament, and without any hesitation or doubt, the Baptist shouts his battle cry: “Let all the world go to bits and we will reconstruct it on the New Testament.”

DIRECT INDIVIDUAL APPROACH TO GOD

When we turn to this New Testament, which is Christ’s guidebook and law for His people, we find that supreme emphasis is everywhere put upon the individual. The individual is segregated from family, from church, from state and from society, from dearest earthly friends or institution, and brought into direct, personal dealings with God. Every one must give account of himself to God. There can be no sponsors or deputies or proxies in such a vital matter. Each one must repent for himself, and believe for himself, and be baptised for himself, and answer to God for himself, both in time and in eternity. The clarion cry of John the Baptist is to the individual, “Think not to say within yourselves, we have Abraham to our father: For I say unto you that God is able of these stones to raise up children unto Abraham. And now also the axe is laid upon the roots of the trees; therefore, every tree that bringeth not forth good fruit is hewn down and cast into the fire.” One man can no more repent and believe and obey Christ for another than he can take the other’s place at God’s judgment bar. Neither persons nor institutions, however dear and powerful, may dare to come between the individual soul and God. “There is one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus.” Let the state and the church, let the institution, however dear, and the person, however near, stand aside, and let the individual soul make its own direct and immediate response to God. One is our pontiff, and his name is Jesus. The undelegated sovereignty of Christ makes it forever impossible for His saving grace to be manipulated by any system of human mediation whatsoever.

The right to private judgment is the crown jewel of humanity, and for any person or institution to dare to come between the soul and God is a blasphemous impertinence and a defamation of the crown rights of the Son of God.

Out of these two fundamental principles, the supreme authority of the Scriptures and the right of private judgment have come all the historic protests in Europe and England and America against unscriptural creeds, polity and rites, and against the unwarranted and impertinent assumption of religious authority over men’s consciences, whether by church or by state. Baptists regard as an enormity any attempt to force the conscience, or to constrain men, by outward penalties, to this or that form of religious belief. Persecution may make men hypocrites, but it will not make them Christians.

INFANT BAPTISM UNTHINKABLE

It follows, inevitably, that Baptists are unalterably opposed to every form of sponsorial religion. If I have fellow Christians in this presence to-day who are the protagonists of infant baptism, they will allow me frankly to say, and certainly I would say it in the most fraternal, Christian spirit, that to Baptists infant baptism is unthinkable from every viewpoint. First of all, Baptists do not find the slightest sanction for infant baptism in the Word of God. That fact, te Baptists, makes infant baptism a most serious question for the consideration of the whole Christian world. Nor is that all. As Baptists see it, infant baptism tends to ritualise Christianity and reduce it to lifeless forms. It tends also and inevitably, as Baptists see it, to the secularising of the church and to the blurring and blotting out of the line of demarcation between the church and the unsaved world.

And since I have thus spoken with unreserved frankness, my honoured Pedobaptist friends in the audience will allow me to say that Baptists solemnly believe that infant baptism, with its implications, has flooded the world and floods it now, with untold evils.

They believe also that it perverts the Scriptural symbolism of baptism; that it attempts the impossible task of performing an act of religious obedience by proxy, and that since it forestalls the individual initiative of the child, it carries within it the germ of persecution, and lays the predicate for the union of church and state, and that it is a Romish tradition and a corner stone for the whole system of popery throughout the world.

I will speak yet another frank word for my beloved Baptist people, to our cherished fellow Christians who are not Baptists, and that word is that our Baptist people believe that, if all the Protestant denominations would once for all put away infant baptism, and come to the full acceptance and faithful practice of New Testament baptism, the unity of all the nonCatholic Christians in the world would be consummated, and that there would not be left one Roman Catholic church on the face of the earth at the expiration of the comparatively short period of another century.

Surely, in the face of these frank statements, our non-Baptist neighbours may apprehend something of the difficulties compelling Baptists when they are asked to enter into official alliances with those who hold such fundamentally different views from those just indicated. We call God to witness that our Baptist people have an unutterable longing for Christian union, and believe Christian union will come, but we are compelled to insist that if this union is to be real and effectivé, it must be based upon a better understanding of the Word of God and a more complete loyalty to the will of Christ as revealed in His Word.

THE ORDINANCES ARE SYMBOLS

Again, to Baptists, the New Testament teaches that salvation through Christ must precede membership in His church, and must precede the observance of the two ordinances in His church, namely, baptism and the Lord’s Supper. These ordinances are for the saved and only for the saved. These two ordinances are not sacramental, but symbolic. ‘They are teaching ordinances, portraying in symbol truths of immeasurable and everlasting moment to humanity. To trifle with these symbols, to pervert their forms and at the same time to pervert the truths they are designed to symbolise, is indeed a most serious matter. Without ceasing and without wavering, Baptists are, in conscience, compelled to contend that these two teaching ordinances shall be maintained in the churches just as they were placed there in the wisdom and authority of Christ. To change these two meaningful symbols is to change their Scriptural intent and content, and thus pervert them, and we solemnly believe, to be the carriers of the most deadly heresies. By our loyalty to Christ, which we hold to be the supreme test of our friendship for Him, we must unyieldingly contend for these two ordinances as they were originally given to Christ’s churches.

To Baptists, the New Testament also clearly teaches that Christ’s church is not only a spiritual body but it is also a pure democracy, all its members being equal, a local congregation, and cannot subject itself to any outside control. Such terms, therefore, as “The American Church,” or “The bishop of this city or state,” sound strangely incongruous to Baptist ears. In the very nature of the case, also, there must be no union between church and state, because their nature and functions are utterly different. Jesus stated the principle in the two sayings, “My kingdom is not of this world,” and “Render unto Cesar the things that are Cesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.” Never, anywhere, in any clime, has a true Baptist been willing, for one minute, for the union of church and state, never for a moment.

Every state church on the earth is a spiritual tyranny. And just as long as there is left upon this earth any state church, in any land, the task of Baptists will that long remain unfinished. Their cry has been and is and must ever be this:

“Let Cesar’s dues be paid To Cesar and his throne; But consciences and souls were made To be the Lord’s alone.”

A FREE CHURCH IN A FREE STATE

That utterance of Jesus, “Render unto Cesar the things that are Czsar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s,” is one of the most revolutionary and history-making utterances that ever fell from those lips divine. That utterance, once for all, marked the divorcement of church and state. It marked a new era for the creeds and deeds of men. It was the sunrise gun of a new day, the echoes of which are to go on and on and on until in every land, whether great or small, the doctrine shall have absolute supremacy everywhere of a free church in a free state.

In behalf of our Baptist people I am compelled to say that forgetfulness of the principles that I have just enumerated, in our judgment, explains many of the religious ills that now afflict the world. All went well with the early churches in their earlier days. They were incomparably triumphant days for the Christian faith. Those early disciples of Jesus, without prestige and worldly power, yet aflame with the love of God and the passion of Christ, went out and shook the pagan Roman Empire from centre to circumference, even in one brief generation. Christ’s religion needs no prop of any kind from any worldly source, and to the degree that it is thus supported it has a millstone hanged about its neck.

AN INCOMPARABLE APOSTASY

Presently there came an incomparable apostasy in the realm of religion, which shrouded the world in spiritual night through long hundreds of years. Constantine, the Emperor, saw something in the religion of Christ’s people which awakened his interest, and now we see him uniting religion to the state and marching up the marble steps of the Emperor’s palace, with the church robed in purple. Thus and there was begun the most baneful misalliance that ever fettered and cursed a suffering world. For long centuries, even from Constantine to Pope Gregory VII, the conflict between church and state waxed stronger and stronger, and the encroachments and usurpations became more deadly and devastating. When Christianity first found its way into the city of the Cesars it lived in cellars and alleys, but when Constantine crowned the union of church and state, the church was stamped with the impress of the Roman idea and fanned with the spirit of the Cesars. Soon we see a Pope emerging, who himself became a Cesar, and soon a group of councillors may be seen gathered around this Pope, and the supreme power of the church is assumed by the Pope and his councillors.

The long blighting record of the medieval ages is simply the working out of that idea. The Pope ere long assumed to be the monarch of the world, making the astounding claim that all kings and potentates were subject unto him. By and by when Pope Gregory VII, better known as Hildebrand, appears, his assumptions are still more astounding. In him the spirit of the Roman church became incarnate and triumphant. He lorded it over parliaments and council chambers, having statesmen to do his bidding, and creating and deposing kings at his will. For example, when the Emperor Henry offended Hildebrand, the latter pronounced against Henry a sentence not only of excommunication but of deposition as Emperor, releasing all Christians from allegiance to him. He made the Emperor do penance by standing in the snow with his bare feet at Canossa, and he wrote his famous letter to William the Conqueror to the effect that the state was subordinate to the church, that the power of the state as compared to the church was as the moon compared to the sun.

This explains the famous saying of Bismarck when Chancellor of Germany, to the German Parliament: “We will never go to Canossa again.” Whoever favours the authority of the church over the state favours the way to Canossa.

When, in the fullness of time, Columbus discovered America, the Pope calmly announced that he would divide the New World into two parts, giving one part to the King of Spain and the other to the King of Portugal. And not only did this great consolidated ecclesiasticism assume to lord it over men’s earthly treasures, but they lorded it over men’s minds, prescribing what men should think and read and write. Nor did such assumption stop with the things of this world, but it laid its hand on the next world, and claimed to have in its possession the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven and the kingdom of purgatory so that it could shut men out of heaven or lift them out of purgatory, thus surpassing in the sweep of its power and in the pride of its autocracy the boldest and most presumptuous ruler that ever sat on a civil throne.

ABSOLUTISM VS. INDIVIDUALISM

The student of history cannot fail to observe that through the long years two ideas have been in endless antagonism—the idea of absolutism and the idea of individualism, the idea of autocracy and the idea of democracy. The idea of autocracy is that supreme power is vested in the few, who, in turn, delegate this power to the many. That was the dominant idea of the Roman Empire, and upon that idea the Cesars built their throne. That idea has found world-wide impression in the realms both civil and ecclesiastical. Often have the two ideas, absolutism versus individualism, autocracy versus democracy, met in battle. Autocracy dared, in the morning of the twentieth century; to crawl out of its ugly lair and to propose to substitute the law of the jungles for the law of human brotherhood. For all time to come the hearts of men will stand aghast upon every thought of this incomparable death drama, and at the same time they will renew the vow that the few shall not presumptuously tyrannise over the many; that the law of human brotherhood and not the law of the jungle shall be given supremacy in all human affairs. And until the principle of democracy, rather than the principle of autocracy, shall be regnant in the realm of religion, our mission shall be commanding and unending.

THE REFORMATION INCOMPLETE

The coming of the sixteenth century was the dawning of a new hope for the world. With that century came the Protestant Reformation. Yonder goes Luther with his theses, which he nails over the old church door in Wittenberg, and the echoes of the mighty deed shake the Papacy, shake Europe, shake the whole world. Luther was joined by Melancthon and Calvin and Zwingli and other mighty leaders.

Just at this point emerges one of the most outstanding anomalies of all history. Although Luther and his compeers protested vigorously against the errors of Rome, yet when these mighty men came out of Rome, and mighty men they were, they brought with them some of the grievous errors of Rome. The Protestant Reformation of the Sixteenth century was sadly incomplete—it was a case of arrested development. Although Luther and his compeers grandly sounded out the battle cry of justification by faith alone, yet they retained the doctrine of infant baptism and a state church. They shrank from the logical conclusions of their own theses.

In Zurich there stands a Statue in honour of Zwingli, in which he is represented with a Bible in one hand and a sword in the other. That statue was the symbol of the union between church and state. The same statue might have been reared to Luther and his fellow reformers. Luther and Melancthon fastened a state church upon Germany, and Zwingli fastened it upon Switzerland. Knox and his associates fastened it upon Scotland. Henry VIII bound it upon England, where it remains even till this very hour. —

These mighty reformers turned out to be persecutors like the Papacy before them. Luther unloosed the dogs of persecution against the struggling and faithful Anabaptists. Calvin burned Servetus, and to such awful deed Melancthon gave his approval. Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, shut the doors of all the Protestant churches, and outlawed the Huguenots. Germany put to death that mighty Baptist leader, Balthaser Hubmaier, while Holland killed her noblest statesman, John of Barneveldt, and condemned to life imprisonment her ablest historian, Hugo Grotius, for conscience’ sake. In England, John Bunyan was kept in jail for twelve long, weary years because of his religion, and when we cross the mighty ocean separating the Old World and the New, we find the early pages of American history crimsoned with the stories of religious persecutions. The early colonies of America were the forum of the working out of the most epochal battles that earth ever knew for the triumph of religious and civil liberty.

Just a brief glance at the struggle in those early colonies must now suffice us. Yonder in Massachusetts, Henry Dunster, the first president of Harvard, was removed from the presidency because he objected to infant baptism. Roger Williams was banished, John Clarke was put in prison, and they publicly whipped Obadiah Holmes on Boston Common. In Connecticut the lands of our Baptist fathers were confiscated and their goods sold to build a meeting house and support a preacher of another denomination. In old Virginia, “mother of states and statesmen,” the battle for religious and civil liberty was waged all over her nobly historic territory, and the final triumph recorded there was such as to write imperishable glory upon the name of Virginia until the last syllable of recorded time. Fines and imprisonments and persecutions were everywhere in evidence in Virginia for conscience’ sake. If you would see a record incomparably interesting, go read the early statutes in Virginia concerning the Established Church and religion, and trace the epic story of the history-making struggles of that early day. If the historic records are to be accredited, those clergymen of the Established Church in Virginia made terrible inroads in collecting fines in Baptist tobacco in that early day. It is quite evident, however, that they did not get all the tobacco.

On and on was the struggle waged by our Baptist fathers for religious liberty in Virginia, in the Carolinas, in Georgia, in Rhode Island and Massachusetts and Connecticut, and elsewhere, with one unyielding contention for unrestricted religious liberty for all men, and with never one wavering note. They dared to be odd, to stand alone, to refuse to conform, though it cost them suffering and even life itself. They dared to defy traditions and customs, and deliberately chose the day of non-conformity, even though in many a case it meant across. They pleaded and suffered, they offered their protests and remonstrances and memorials, and, thank God, mighty statesmen were won to their contention, Washington and Jefferson and Madison and Patrick Henry, and many others, until at last it was written into our country’s Constitution that church and state must in this land be forever separate and free, that neither must ever trespass upon the distinctive functions of the other. It was pre-eminently a Baptist achievement.

Glad are our Baptist people to pay their grateful tribute to their fellow Christians of other religious communions for all their sympathy and help in this sublime achievement. Candour compels me to repeat that much of the sympathy of other religious leaders in that early struggle was on the side of legalised ecclesiastical privilege. Much of the time were Baptists pitiably lonely in their age-long struggle. We would now and always make our most grateful acknowledgment to any and all who came to the side of our Baptist fathers, whether early or late, in this destiny-determining struggle. But I take it that every informed man on the subject, whatever his religious faith, will be willing to pay tribute to our Baptist people as being the chief instrumentality in God’s hands in winning the battle in America for religious liberty. Do you recall Tennyson’s little poem, in which he sets out the history of the seed of freedom? Catch its philosophy:

Once in a golden hour, I cast to earth a seed, Up there came a flower, The people said, a weed.

To and fro they went, Through my garden bower, And muttering discontent, Cursed me and my flower.

Then it grew so tall, It wore a crown of light, But thieves from o’er the wall, Stole the seed by night.

Sowed it far and wide, By every town and tower, Till all the people cried, ‘Splendid is the flower.’

Read my little fable: He who runs may read, Most can grow the flowers now, For all have got the seed.”

Very well, we are very happy for all our fellow religionists of every denomination and creed to have this splendid flower of religious liberty, but you will allow us to remind you that you got the seed in our Baptist garden. We are very happy for you to have it; now let us all make the best of it and the most of it.

THE PRESENT CALL

And now, my fellow Christians, and fellow citizens, what is the present call to us in connection with the priceless principle of religious liberty? That principle, with all the history and heritage accompanying it, imposes upon us obligations to the last degree meaningful and responsible. Let us to-day and forever be highly resolved that the principle of religious liberty shall, please God, be preserved inviolate through all our days and the days of those who come after us. Liberty has both its perils and its obligations. We are to see to it that our attitude toward liberty, both re-ligious and civil, both as Christians and as citizens, is an attitude consistent and constructive and worthy. We are to “Render unto Cesar the things that are Cesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.”” We are members of the two realms, the civil and the religious, and are faithfully to render unto each all that each should receive at our hands; we are to be alertly watchful, day and night, that liberty, both religious and civil, shall be nowhere prostituted and mistreated. Every perversion and misuse of liberty tends by that much to jeopardise both church and state.

There comes now the clarion call to us to be the right kind of citizens. Happily, the record of our Baptist people toward civil government has been a record of unfading honour. Their love and loyalty to country have not been put to shame in any land. In the long list of published Tories in connection with the Revolutionary War there was not one Baptist name.

LIBERTY NOT ABUSED

It behooves us now and ever to see to it that liberty is not abused. Well may we listen to the call of Paul, that mightiest Christian of the long centuries, as he says: “Brethren, ye have been called unto liberty; only use not liberty for an occasion to the flesh, but by love serve one another.” This ringing declaration should bé heard and heeded by every class and condition of people throughout all our wide-stretching nation.

It is the word to be heeded by religious teachers, and by editors, and by legislators, and by everybody else. Nowhere is liberty to be used “for an occasion to the flesh.” We will take free speech and a free press, with all their excrescences and perils, because of the high meaning of freedom, but we are to set ourselves with all diligence not to use these great privileges in the shaming of liberty. A free press—how often does it pervert its high privilege! Again and again, it may be seen dragging itself through all the sewers of the social order, bringing to light the moral cancers and leprosies of our poor world and glaringly exhibiting them to the gaze even of responsive youth and’ childhood. The editor’s task, whether in the realm of church or state, is an immeasurably responsible one. These editors, side by side with the moral and religious teachers of the country, are so to magnify the ballot box, a free press, free schools, the courts, the majesty of law and reverence for all properly accredited authority that our civilisation may not be built on the shifting sands, but on the secure and enduring foundations of righteousness.

Let us remember that lawlessness, wherever found and whatever its form, is as the pestilence that walketh in darkness and the destruction that wasteth at noonday. Let us remember that he who is willing for law to be violated is an offender against the majesty of law as really as he who actually violates law. The spirit of law is the spirit of civilisation. Liberty without law is anarchy. Liberty against law is rebellion. Liberty limited by law is the formula of civilisation.

HUMANE AND RIGHTEOUS LAWS

Challenging to the highest degree is the call that comes to legislators. They are to see to it continually, in all their legislative efforts, that their supreme concern is for the highest welfare of the people. Laws humane and righteous are to be fashioned and then to be faithfully regarded. Men are playing with fire if they lightly fashion their country’s laws and then trifle in their obedience to such laws. Indeed, all citizens, the humblest and the most prominent alike, are called to give their best thought to the maintenance of righteousness everywhere. Much truth is there in the widely quoted saying: “Our country is afflicted with the bad citizenship of good men.” The saying points its own clear lesson. ‘When the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice, but when the wicked bear rule, the people mourn.” ‘The people, all the people, are inexorably responsible for the laws, the ideals, and the spirit that are necessary for the making of a great and enduring civilisation. Every man of us is to remember that it is righteousness that exalteth a nation, and that it is sin that reproaches and destroys a nation.

God does not raise up a nation to go selfishly strutting and forgetful of the high interests of humanity. National selfishness leads to destruction as truly as does individual selfishness. Nations can no more live to themselves than can individuals. Humanity is bound up together in the big bundle of life. The world is now one big neighbourhood. There are no longer any hermit nations. National isolation is no longer possible in the earth. The markets of the world instantly register every commercial change. An earthquake in Asia is at once registered in Washington City. The people on one side of the world may not dare to be indifferent to the people on the other side. Every man of us is called to be a world citizen, and to think and act in world terms. The nation that insists upon asking that old murderous question of Cain, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” the question of the profiteer and the question of the slacker, is a nation marked for decay and doom and death. The parable of the good Samaritan is heaven’s law for nations as well as for individuals. Some things are worth dying for, and if they are worth dying for they are worth living for. The poet was right when he sang:

“Though love repine and reason chefe, There comes a voice without reply, Tis man’s perdition to be safe, When for the truth he ought to die.”

THINGS WORTH DYING FOR

When this nation went into the world war a little while ago, after her long and patient and fruitless effort to find another way of conserving righteousness, the note was sounded in every nook and corner of our country that some things in this world are worth dying for, and if they are worth dying for they are worth living for. What are some of the things worth dying for? The sanctity of womanhood is worth dying for. The safety of childhood is worth dying for, and when Germany put to death that first helpless Belgian child she was marked for defeat and doom.

The integrity of one’s country is worth dying for. And, please God, the freedom and honour of the United States of America are worth dying for. If the great things of life are worth dying for, they are surely worth living for. Our great country may not dare to isolate herself from the rest of the world, and selfishly say: “We propose to live and to die to ourselves, leaving all the other nations with their weaknesses and burdens and sufferings to go their ways without our help.” ‘This nation cannot pursue any such policy and expect the favour of God. Myriads of voices, both from the living and the dead, summon us to a higher and better way. Happy am I to believe that God has His prophets not only in the pulpits of the churches but also in the school room, in the editor’s chair, in the halls of legislation, in the marts of commerce, in the realms of literature. Tennyson was a prophet, when in “Locksley Hall,” he sang:

For I dipped into the future, far as human eye could see, Saw the vision of the world, and all the wonder that would be; Saw the heavens filled with commerce, argosies of magic sails, Pilots of the purple twilight, dropping down with costly bales; Heard the heavens filled with shouting, and there rained a ghastly dew From the nation’s airy navies, grappling in the central blue; Far along the world-wide whisper of the south wind rushing warm, With the standards of the people plunging through the thunder storm. Till the war drums throbbed no longer, and the battleflags were furled, In the Parliament of Man, the Federation of the World.”

A LEAGUE OF NATIONS

Tennyson believed in a league of nations, and well might he so believe, because God is on His righteous throne, and inflexible are His purposes touching righteousness and peace, for a weary, sinning, suffering, dying world. Standing here to-day on the steps of our Nation’s capitol, hard by the chamber of the Senate of the United States, I dare to say as a citizen and as a Christian teacher, that the moral forces of the United States of America, without regard to political parties, will never rest until there is a worthy League of Nations. I dare to express also the unhesitating belief that the unquestioned majorities of both great political parties in this country regard the delay in the working out of a League of Nations as a national and worldwide tragedy.

The moral and religious forces of this country could not be supine and inactive as long as the saloon, the chief rendezvous of small politicians, that chronic criminal and standing anachronism of our modern civilisation, was legally sponsored by the state. I can certify all the politicians of all the political parties that the legalised saloon has gone from American life, and gone to stay. Likewise, I can certify the men of all political parties, without any reference to partisan politics, that the same moral and religious forces of this country, because of the inexorable moral issues involved, cannot be silent and will not be silent until there is put forth a League of Nations that will strive with all its might to put an end to the diabolism and measureless horrors of war. I thank God that the stricken man yonder in the White House has pleaded long and is pleading yet that our nation will take her full part with the others for the bringing in of that blessed day when wars shall cease to the ends of the earth.

The recent World War calls to us with a voice surpassingly appealing and responsible. Surely Alfred Noyes voices the true desire for us:

Make firm, O God, the peace our dead have won, For folly shakes the tinsel on its head, And points us back to darkness and to hell, Cackling, ‘Beware of visions,’ while our dead Still cry, ‘It was for visions that we fell.’ They never knew the secret game of power, All that this earth can give they thrust aside, They crowded all their youth into an hour, And for fleeting dream of right, they died. Oh, if we fail them in that awful trust, How should we bear those voices from the dust?

THE RIGHT KIND OF CHRISTIANS

This noble doctrine and heritage of religious liberty calls to us imperiously to be the right kind of Christians. Let us never forget that a democracy, whether civil or religious, has not only its perils, but has also its unescapable obligations. A democracy calls for intelligence. The sure foundations of states must be laid, not in ignorance, but in knowledge. It is of the last importance that those who rule shall be properly trained. In a democracy, a government of the people, for the people, and by the people, the people are the rulers, and the people, all the people, are to be informed and trained.

My fellow Christians, we must hark back to our Christian schools, and see to it that these schools are put on worthy and enduring foundations. A democracy needs more than intelligence; it needs Christ. He is the light of the world, nor is there any other sufficient light for the world. He is the solution of the world’s complex questions, the one adequate Helper for its dire needs, the one only sufficient Saviour for our sinning race. Our schools are afresh to take note of this supreme fact, and they are to be fundamentally and aggressively Christian. Wrong education broughton the recent World War. Such education will always lead to disaster.

Pungent were the recent words of Mr. Lloyd George:

“The most formidable foe that we had to fight in Germany was not the arsenals of Krupp, but the schools of Germany.” The educational centre of the world will no longer be in the Old World, but because of the great War, such centre will henceforth be in this New World of America. We must build here institutions of learning that will be shot through and through with the principles and motives of Christ, the one Master over all mankind.

THE CHRISTIAN SCHOOL

The time has come when, as never before, our beloved denomination should worthily go out to its world task as a teaching denomination. That means that there should be a crusade throughout all our borders for the vitalising and strengthening of our Christian schools. The only complete education, in the nature of the case, is Christian education, because man is a tripartite being. By the very genius of our government, education by the state cannot be complete. Wisdom has fled from us if we fail to magnify, and magnify now, our Christian schools. These schools go to the foundation of all the life of the people. They are indispensable to the highest efficiency of the churches. Their inspirational influences are of untold value to the schools conducted by the state, to which schools also we must’ ever give our best support. It matters very much, do you not agree, who shall be the leaders, and what the standards in the affairs of civil government and in the realm of business life? One recalls the pithy saying of Napoleon to Marshal Ney: “An army of deer led by a lion is better than an army of lions led by a deer.” Our Christian schools are to train not only our religious leaders but hosts of our leaders in the civil and business realm as well.

The one transcending inspiring influence in civilisation is the Christian religion. By all means, let the teachers and trustees and student bodies of all our Christian schools remember this supremely important fact, that civilisation without Christianity is doomed. Let there be no pagan ideals in our Christian schools, and no hesitation or apology for the insistence that the one hope for the individual, the one hope for society, for civilisation, is in the Christian religion. If ever the drum beat of duty sounded clearly, it is calling to us now to strengthen and magnify our Christian schools.

THE TASK OF EVANGELISM

Preceding and accompanying the task of building our Christian schools, we must keep faithfully and practically in mind our primary task of evangelism, the work of winning souls from sin unto salvation, from Satan unto God. This work takes precedence of all other work in the Christian programme. Salvation for sinners is through Jesus Christ alone, nor is there any other name or way under heaven whereby they may be saved. Our churches, our schools, our religious papers, our hospitals, every organisation and agency of the churches should be kept aflame with the passion of New Testament evangelism. Our cities and towns and villages and country places are to echo continually with the sermons and songs of the gospel evangel. The people, high and low, rich and poor, the foreigners, all the people are to be faithfully told of Jesus and His great salvation, and entreated to come unto Him to be saved by Him and to become His fellow workers. The only sufficient solvent for all the questions in America, individual, social, economic, industrial, financial, political, educational, moral and religious, is to be found in the Saviourhood and Lordship of Jesus Christ.

“Give is a watchword for the hour, A thrilling word, a word of power; A battle cry, a flaming breath, That calls to conquest or to death; A word to rouse the church from rest, To heed its Master’s high behest, The call is given, Ye hosts, arise; Our watchword is Evangelise! The glad Evangel now proclaim, Through all the earth in Jesus’ name, This word is ringing through the skies, Evangelise! Evangelise! To dying men, a fallen race, Make known the gift of Gospel Grace; The world that now in darkness lies, Evangelise! Evangelise!”’

While thus caring for the homeland, we are at the same time to see to it that our programme is co-extensive with Christ’s programme for the whole world. The whole world is our field, nor may we, with impunity, dare to be indifferent to any section, however remote, not a whit less than that, and with our plans sweeping the whole earth, we are to go forth with believing faith and obedient service, to seek to bring all humanity, both near and far, to the faith and service of Him who came to be the propitiation for our sins, and not for ours only, but also for the sins of the whole world.

His commission covers the whole world and reaches to every human being. Souls in China, and India, and Japan, and Europe, and Africa, and the islands of the sea, are as precious to Him as souls in the United States. By the love we bear our Saviour, by the love we bear our fellows, by the greatness and preciousness of the trust committed to us, we are bound to take all the world upon our hearts and to consecrate our utmost strength to bring all humanity under the sway of Christ’s redeeming love. Let us go to such task, saying with the immortal Wesley, “The world is my parish,” and with him may we also be able to say, “And best of all, God is with us.”

A GLORIOUS DAY

Glorious it is, my fellow Christians, to be living in such a day as this, if only we shall live as we ought to live. Irresistible is the conviction that the immediate future is packed with amazing possibilities. We can understand the cry of Rupert Brooke as he sailed from Gallipoli, “Now God be thanked who hath matched us with this hour!” The day of the reign of the common people is everywhere coming like the rising tides of the ocean. The people are everywhere breaking with feudalism. Autocracy is passing, whether it be civil or ecclesiastical. Democracy is the goal toward which all feet are travelling, whether in state or in church.

The demands upon us now are enough to make an archangel tremble. Themistocles had a way of saying that he could not sleep at night for thinking of Marathon. What was Marathon compared to a day like this? John C. Calhoun, long years ago, stood there and said to his fellow workers in the National Congress: “I beg you to lift up your eyes to the level of the conditions that now confront the American republic.” Great as was that day spoken of by Mr. Calhoun, it was as a tiny babe beside a giant compared to the day that now confronts you and me. Will we be alert to see our day and faithful enough to measure up to its high demands?

THE PRICE TO BE PAID

Are we willing to pay the price that must be paid to secure for humanity the blessings they need to have? We say that we have seen God in the face of Jesus Christ, that we have been born again, that we are the true friends of Christ, and would make proof of our friendship for Him by doing His will. Well, then, what manner of people ought we to be in all holy living and godliness? Surely we should be a holy people, remembering the apostolic characterisation, “Ye are a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, an holy nation, a peculiar people: That we should shew forth the praises of Him who hath called you out of darkness into His marvellous light, who in time past were not a people but are now the people of God.”

Let us look again to the strange passion and power of the early Christians. They paid the price for spiritual power. Mark well this record: “And they overcame him by the blood of the Lamb, and by the word of their testimony; and they loved not their lives unto the death.” O my fellow Christians, if we are to be in the true succession of the mighty days and deeds of the early Christian era, or of those mighty days and deeds of our Baptist fathers in later days, then selfish ease must be utterly renounced for Christ and His cause, and our every gift and grace and power utterly dominated by the dynamic of His cross. Standing here in the shadow of our country’s capitol, compassed about as we are with so great a cloud of witnesses, let us to-day renew our pledge to God, and to one another, that we will give our best to church and to state, to God and to humanity, by His grace and power, until we fall on the last sleep.

If in such spirit we will give ourselves to all the duties that await us, then we may go our ways, singing more vehemently than our fathers sang them, those lines of Whittier:

“Our fathers to their graves have gone, Their strife is passed, their triumphs won; But greater tasks await the race Which comes to take their honoured place, A moral warfare with the crime And folly of an evil time. “So let it be, in God’s own sight, We gird us for the coming fight; And strong in Him whose cause is ours, In conflict with unholy powers, We grasp the weapons He has given, The light and truth and love of Heaven.”

Baptists at the end of choice, II

December 21, 2022when does free choice stop gaining happiness?

We left off asking why is liberalism being criticized on all sides, a mere thirty years after it was supposed to be the end state of human affairs?

The internet seems to be the most significant change. The internet gave us unprecedented freedom of choice. You could choose your own identity. You could speak freely without consequence. “[A] group of social outcasts could come together to form a chosen family.” You could watch whatever sex you wanted. You could Google all the facts of a liberal arts education. The masses suddenly had more liberty of choice than at any time in history.

But a massive expansion of choice and free speech did not give us Utopia. It gave us 4Chan and Twitter.

Worse, the internet showed the American dream – a dream of curated consumption – wasn’t universal. A good degree, a fulfilling career, a happy marriage, the house with a picket fence, a few kids: these were once seen as the just desserts of all moral, educated Americans. But the internet showed us many moral and educated Americans did not receive their expected birthright. You can, in fact, overspend on education. You can wreck generations of your family by going to Baylor.

And the education available to you has been colonized by a theory of sociological constraints. Whatever freedoms you appear to have, you’ll be taught, they’re steeped in evil. You can’t escape the ugly history that led to today. Freedom and autonomy aren’t liberal arts, to be practiced, but the spoils of complicity and guilt. Your racist job funds a commute to a racist suburb, where you live in your racist home, within your racist marriage – and your only atonement is to do the work.

College degree or not, all of us have had an apocalypse about sex. The old taboos are subject to instant replay. And contrary to what authorities said, the video shows convincing evidence that people enjoy them.

But if the internet shows you infinite identities, and each of them might make you happy, how do you find out besides trying all of them? Psychologists have long noted that people who lack choices will often fight for them, but “many choices can be psychologically aversive.” Social media has had a particularly negative effect on adolescent girls. And for those girls, there has been a sudden jump in nonbinary self-identification, apparently responding to these new choices. Some have reported that body dysmorphia spreads socially.

Even if you could process the sheer number of intersectional choices, there is another problem: identity isn’t self-constructed. It depends, in some way, on the thoughts and actions of others. If “the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life,” what happens when others won’t cooperate in your definitions? You could be legally free to have a same-sex marriage, but religious critics remain. What if you’re freed from your assigned gender, but others don’t agree you’re different from natal women in important ways?

So if the world’s array of choices seemed like a glorious cornucopia to Anthony Kennedy, most of us will not – cannot – be made happy by more choosing. Aaron Renn posted a snippet from the Anarchist Library about the meaning of 2011’s Occupy Wall Street protests:

“The true content of Occupy Wall Street was not the demand[s]… but disgust with the life we’re forced to live. Disgust with a life in which we’re all alone, alone facing the necessity for each one to make a living, house oneself, feed oneself, realize one’s potential, and attend to one’s health, by oneself. … At last it was possible to grasp … our equal reduction to the status of entrepreneurs of the self.

The Preacher of Ecclesiastes said as much: “Vanity! What do people gain from all their labors at which they toil under the sun?” The core of Baptist political theory is the Bible, including the wisdom of Ecclesiastes.

So as much as Baptists have benefited and agree with the Declaration’s “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” for common government, liberty and the pursuit of happiness aren’t happiness. Freedom to choose does not prevent alienation. Amazon Prime subscriptions don’t produce a body politic.

The apocalypse of choice is that after all of your choice is exhausted, you may remain alienated. Miserable. And then what?

And then some people turn to force – some kind of illiberalsim.

Pseudonymous blogger NS Lyons captured the seemingly inconsistent demands of today’s liberalism: individualism is so sacred, it requires force to overcome natural and political obstacles.

From this perspective it is more obvious why the amorphous ideology referred to as “Wokeness” so often seems mixed up and chaotically self-contradictory: it is the confused response to two opposite instincts. On the one hand it is actually a kind of anti-liberal reactionary movement … But, on the other hand, it simultaneously attempts to continue embracing the boundless autonomy of individual choice as its most sacred principle … And this hyper-individualism has now collided head first with the technological revolution, which increasingly positions itself as offering hope for the boundless potential necessary to escape from any natural limits whatsoever, including by fracturing any solid definition of what we once thought it meant to be human.

How should we react to the apparent ‘end of liberty?’

That’s the next post.

Baptists at the end of choice

October 27, 2022For the past few years, conservatives have been debating whether they are “post-liberal”. A recent article in The Federalist says we need to stop calling ourselves conservatives. “They should … start thinking of themselves as radicals, restorationists, and counterrevolutionaries.”

You could mark the start of this debate to a pair of articles in First Things, in 2019. One was Against the Dead Consensus, and then the more pointed Against David French-ism.

Are conservative Baptists post-liberal?

In J. Gresham Machen’s Christianity and Liberalism, liberalism was on the other side of Christianity, and those categories have stuck for a century. So “post-liberal” might appeal to Southern Baptists of today.

But these aren’t just critics of liberals. They’re critics of ‘liberal democracy,’ the Western political tradition. So the post-liberal debate is not about ‘the libs,’ it’s about liberty.

And it would be a big deal if Baptists are post-liberty.

Our Baptist tradition is steeped in congregationalism and democracy. If liberalism is fundamentally flawed, can you still be part of a spiritual democracy?

Even asking seems taboo. For most of my life, it would have been pointless. The Soviet Union collapsed. China seemed like it could be bribed into freedom. The most celebrated companies ran Super Bowl ads based on 1984, against fascism and conformity. Racial inequality seemed to be fading, along with the War of the Sexes.

Liberalism was so successful, theorists got a little punchy. In 1992, Francis Fukuyama wrote that we’d turned the corner of an epoch; we’d reached “the end-point of mankind’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government.”

Today, that end-point seems less universal. China took our money but not our values. Afghanistan took our arms but not our democracy. Russia—once so eager for American advisors—has declared war against the West.

Even in the West, the home of the tradition, liberalism is having a rough go. To give only one example, in the US, the Republican base seems to support right-leaning social policy more than lazziez faire economics. But Republicans continue to focus on economics, even where it underperforms. But in the social arena, educated conservative “elites” lost the public meanings of ‘marriage,’ ‘man,’ and ‘woman’ in about a decade. These ideas hadn’t been up for serious debate at any point in recorded history.

Maybe democracy wasn’t so natural and universal. And maybe all that freedom of choice doesn’t create human capital. Maybe endless choice isn’t the key to more Ivy League students or FAANG software engineers.

But this has left many Conservatives confounded. They believed they were selling something everybody wants; a universal freedom, Fukuyama-like. Freedom and liberty have motivated our politics for centuries.

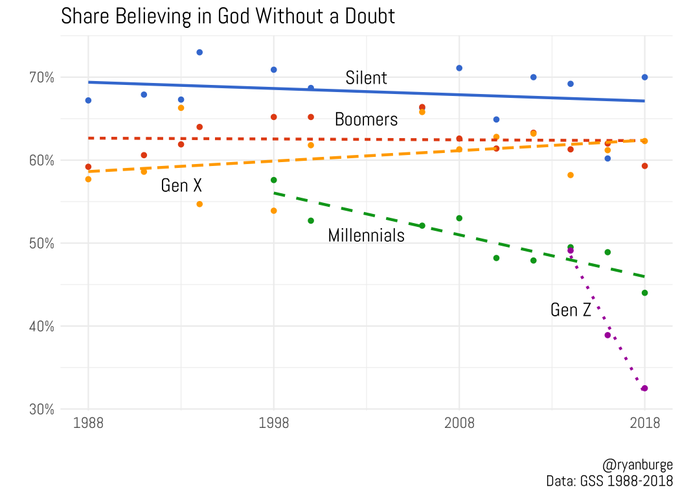

But in 2022, young Americans are embracing atheism and soft-totalitarianism in unprecedented numbers.

If conservatives can’t sell freedom, for goodness sake, are they bad at persuasion or is the game rigged?

Baptists and the Liberal Consensus

To understand the size of the question, you must understand how long “liberalism” has been the consensus. In 1215, rebel English noblemen swore to “stand fast for the liberty of the church and the realm,” and in a few months had obtained the Magna Carta from King John. Nearly ever since, English speakers have seen “more liberty” as something good.

Yet this love of freedom arose among socially conservative people. Conservatives, says Roger Scruton, believe “the social world emerges through free association, rooted in friendship and community life.” The most important identities and relationships are voluntary and community-based, not state-driven.

Of course, some people will use their liberty to make bad choices. Liberalism often tries to curb bad choices with education. Today, a “liberal arts education,” is vapidly promised by every two-bit college. But for centuries, a liberal arts education meant giving people the facts and skills necessary to live as a man or woman with freedom.

This created a Western, liberal consensus: if you give people all the information they need, and freedom to express their will, the majority will choose better outcomes. Right-liberals and left-liberals disagreed about the best choices. But they agreed that legitimate government reflected the will—the choices—of its people.

Baptists increasingly found a home in this liberal consensus. Baptists are democratic congregationalists, by conviction. Other churches locate authority in ministers, sessions, Bishops or Popes. But Baptists say the keys to the Kingdom are given to the local church. The majority of members (whether male or female) are the Baptists’ ultimate human authorities. Baptists believe democracy is not just useful, it is divinely required. But the distinction between Baptist democracy and civil democracy has not been explored, causing many to treat the two as the same thing.

Baptists also believe strongly in liberty, especially religious liberty. Early Baptists taught that kings have no power to punish wrong beliefs, and limited power over acts of legitimate worship. John Leland, a notable early-American Baptist, said the government’s rules should apply equally to all faiths: government “rightly formed … embraces Pagans, Jews, Mahometans and Christians, within its fostering arms.” Good government, he said, “promotes the man of talents and integrity, without inquiring after his religion [&] impartially protects all of them.” In other words, if Baptist ideas swept politics, religious beliefs wouldn’t affect anyone’s capacity to participate in government.

A third Baptist distinctive says the Church should not rely on civil power to achieve the Church’s work. According to the Baptist Faith & Message:

The church should not resort to the civil power to carry on its work. The gospel of Christ contemplates spiritual means alone for the pursuit of its ends. The state has no right to impose penalties for religious opinions of any kind. The state has no right to impose taxes for the support of any form of religion.

Thomas Jefferson famously wrote the Baptists of Danbury, Connecticut, about their shared commitments. He coined a phase, that the then-new Constitution had erected “a wall of separation between Church & State.” “A wall of separation” wasn’t in the Constitution, and it wasn’t a theological term of art. Jefferson might have been paraphrasing Roger Williams’ analogy of the church as a ‘walled garden’ that keeps out the rest of the world. But at least during the Baptist Faith & Message era, Baptists have picked up the phrase, affirming that they do believe Church and State should be separate.

Given these connections, perhaps it is no coincidence that Baptists reached their cultural apex around the same time liberal democracy reached its own.

Baptist theorists also got a little punchy, talking about their new epoch. Indeed, it is hard to read Russell Moore’s 2004 book, The Kingdom of Christ: The New Evangelical Perspective, without sensing the similarities to Fukuyama.

Moore was then a quickly-rising Southern Baptist professor, so conservative as to sometimes extoll “biblical patriarchy.” In his published thesis, Moore predicted a rapidly building “consensus [that] offers a renewed theological foundation for evangelical engagement in the social and political realms.” If the end consensus of human government was liberal democracy, Moore hoped that the final consensus of evangelicalism had arrived, too—and it was more-or-less Baptist. Using ‘gospel centrality,’ Moore predicted the death of evangelical parochialism, especially the “Bible Belt.” The schisms of the past would be internalized and minimized, while culture would see “cheerful warriors” engaged in “public witness” and “cultural engagement.” Evangelical Baptists could become the universal, democratic religion of a universal, democratic epoch.

But looking back, the “consensus” role that Moore coveted was the other American cultural Christianity: the civil religion of educated liberalism. They planned to step into the position vacated by Mainline churches in the 1960s.

Instead, Moore abandoned the Southern Baptist Convention in 2020, calling it a “gerontocracy,” and even a “criminal conspiracy” in 2022.

So, like Fukuyama, Moore’s prediction of a new epoch was deeply flawed. Much of the work built on its unsteady foundation has collapsed into an intra-Evangelical culture war. Moore himself has repositioned as an editor at Christianity Today, trying to ‘save Evangelicalism from itself,’ and recently talked of “crucify[ing]” evangelicalism. It is hard to imagine his predecessor Carl FH Henry making such calls.

Why is liberalism being criticized on all sides, a mere thirty years after it arrived as the victor over history? That’s the next post.

Is this the next Executive Committee CEO?

October 06, 2022I published a video on my short campaign for President of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Executive Committee.

Six, Actionable Ideas If I Were SBCEC CEO:

- TRANSPARENT SALARY DISCLOSURE

- TRANSPARENT 990-LEVEL FINANCIALS

- TRANSPARENT BOARDS DECIDE, NOT COMMITTEES

- ACCOUNTABILITY – ALL TRUSTEES ARE SBC TRUSTEES

- ACCOUNTABILITY – REASSESS GROUP EXEMPTION LETTER

- ACCOUNTABLE, TRANSPARENT & INDEPENDENT INVESTIGATIONS

French and DeYoung

December 30, 2021Have you ever run into someone tipsy with anger? The Romans used to say, “in vino, veritas,” but sometimes it’s anger, not alcohol, which lowers inhibitions. A little bump or shake, and the irritated person uncorks with something they’ve been dying to let go.

Consider David French’s recent exchange with Kevin DeYoung.

DeYoung wrote a mild criticism of evangelical criticism. Even valid jeremiads, suggests KDY, can descend into claims that “those people” hold their views because they are “those kind of people.” CS Lewis coined it “Bulverism,” where a critic stops showing why a view is wrong and turns to why the wrong kind of person holds the view. At some point, “[t]here is no persuasion,” of the target, “only pique and annoyance,” says DeYoung. He suggests the rhythms of church life are a more productive method of self-criticism, instead of “another critique of the church in your inbox on Sunday morning.”

DeYoung went out of his way to say that French’s concerns are valid. He criticized French’s abandonment of persuasion. There was room for French to agree that DeYoung’s concerns are valid but disagree that his methods were unhelpful.

But French responded with hostility. French said DeYoung was absurdly unfair and inaccurate, torching’ a ‘straw man’ characterization of French’s work.

So to avoid mischaracterization, what does French say is his driving thesis? In tweet four, he lays it out clearly: ‘White Evangelical theologies’ have a ‘disproportionate commitment’ to Republicans and ‘the culture of the South.’ DeYoung concedes that people can forsake theological principle under social pressure, and even that it is important to criticize those who do.

If everyone agrees the concern is possible, how does French say we should decide? How would we know if there’s a disproportionate commitment to something that isn’t religious principle? In tweets 2 and 3, French says white Evangelicals have “propositions” that “don’t flow naturally” from their theology. Their positions on ‘Trumpism, anti-masking, anti-vaccine and immigration restrictionism’ don’t flow from theological claims, but political or social claims.

So the issue is multidisciplinary: do the politics follow from the theology? You’d be forgiven in thinking there must be a multidisciplinary answer.

Yet French says few theologians have the chops to speak up. “Sadly, when I see pastors wade in on matters of law/policy, it is rare to see superior insight. And when I do it’s because of a degree of committed study that is highly unusual.”

So who can pass judgment? Lawyers and sociologists, perhaps. “Those of us who know law and policy on the other hand, know where ideas come from and transparently, obviously know that many (not all!) of the political positions that characterize white Evangelicals don’t have any meaningful Evangelical theological origin at all.”

David uses qualified immunity – a legal doctrine that limits when government officials can be personally sued for misconduct – as an example of this qualification gap. He says that Evangelicals support it disproportionately, which I question; when evangelicals talk to me about qualified immunity, they use terms that would make the Cato Institute smile. Evangelicals are eager to hold officials accountable for misconduct. But maybe these are just anecdotes; maybe evangelicals do support qualified immunity at radical levels. Do their political actions contradict their stated theology?

It’s revealing that French does not assert any violation of a theological rule. Rather, French says the theology practitioner has nothing to contribute to his point. “What’s the pastoral insight here as to why a judge-made doctrine that gutted part of the Klan acts should receive disproportionate Evangelical support?” The answer to the rhetorical question is supposed to be “none.” In a theo-political crisis, French says the meaningful insight comes from careful students of law and social science, not students of theology.

So how will the reader know that Evangelicals are pursuing politics at odds with their theology? When “those of us who know law and policy” say so. Those who disagree are (likely to be) people without committed study, people without superior insight, people who don’t know where their ideas even come from. In the end, French doubled down on the Bulverism; people who disagree with his take are often the wrong kind of people.

But let’s go beyond the Bulverism and note that French’s argument took a serious deconstructionist turn. He is no longer asking whether Evangelical theology accounts for political concepts but asking if theology submits to political conclusions.

Of course, French is not saying the Bible is untrue. But he is at the next layer of the authority question: if the words are true, whose theology says what they mean? Jonathan Edwards, slave owner? Paige Patterson, interrogator? Beth Moore, lector? Jemar Tisby, anti-racist? Rather than settle the argument, it’s easier to take a shortcut: “those of us who know law and policy” decide, because theology isn’t involved. But why would anyone think theo-political questions don’t have theo-political answers?

This demand that Evangelical theologies must submit to specialty viewpoints isn’t new. What came to be known as “theological liberalism” was never limited to saying the Bible was “untrue” or “errant.” Rather, the Mainline came to doubt their own ability to understand and apply Biblical truth. If the Bible’s words are indeterminate or silent, if all the evangelical creeds are held at bay as equally unsure, then there must be something else making the decision, often some claim about science, or sociology, or political theory. J. Gresham Machen described the problem of “equal uncertainty” about the creeds in his 1931 classic, “Christianity and Liberalism”:

“The objection involves an out-and-out skepticism. If all creeds are equally true, then since they are contradictory to one another, they are all equally false, or at least equally uncertain. We are indulging, therefore in a mere juggling with words. To say that all creeds are equally true, and that they are based upon experience, is merely to fall back upon that agnosticism which fifty years ago was regarded as the deadliest enemy of the church. The enemy has not really been changed into a friend merely because he has been received within the camp.”

In the (human) law, that kind of uncertainty produced “legal realism.” The realists didn’t deny the law was true, they rejected formalist accounts of the law. According to the realists, humans weren’t applying legal principles to facts, as they claim to do; the rules were indeterminate and open to a wide range of contradictory outcomes. Rather, you could understand the law by seeing facts and outcomes. To the realists, “[b]efore rules, were facts; in the beginning was not a Word, but a Doing. Behind decisions stand judges…as men they have human backgrounds. Beyond rules, again, lie effects.” 1

The effects and outcomes became the wrapper of truth around the vague, indeterminate words of the law.

And here lies the nub: to the textual realist, it is all too easy for the observable effects to become the analytical tools, the real universal principles. Lickety-split, the “true truth” is not the text, but observations and judgments about the outcomes. If our texts can’t compel the right outcomes, we must settle disagreements by resorting to theories that decide for us – the theories that “help us see effects of sin” where our doctrines do not.

Like the scholars raised in the Mainline a century ago, today’s Evangelical scholastics are shaken in their beliefs about Evangelical authority. It isn’t a repeat of Machen’s 1920s, but it rhymes. Some are grasping for truth beyond the reach of theology, where the Evangelical theological parochialisms are all the same.

And that’s old-fashioned theological liberalism.

-